Takashi Hinoda

このウェブサイトは手色形楽(しゅしきけいがく)の作家、日野田崇の作品を紹介するものです。

This website introduces an artist,Takashi Hinoda who works in Hands on Visionamusement..

このウェブサイトは手色形楽(しゅしきけいがく)の作家、日野田崇の作品を紹介するものです。

This website introduces an artist,Takashi Hinoda who works in Hands on Visionamusement..

KLEI Magazine, March,2013, Netherlands

keramisch magazine KLEI 2013 March

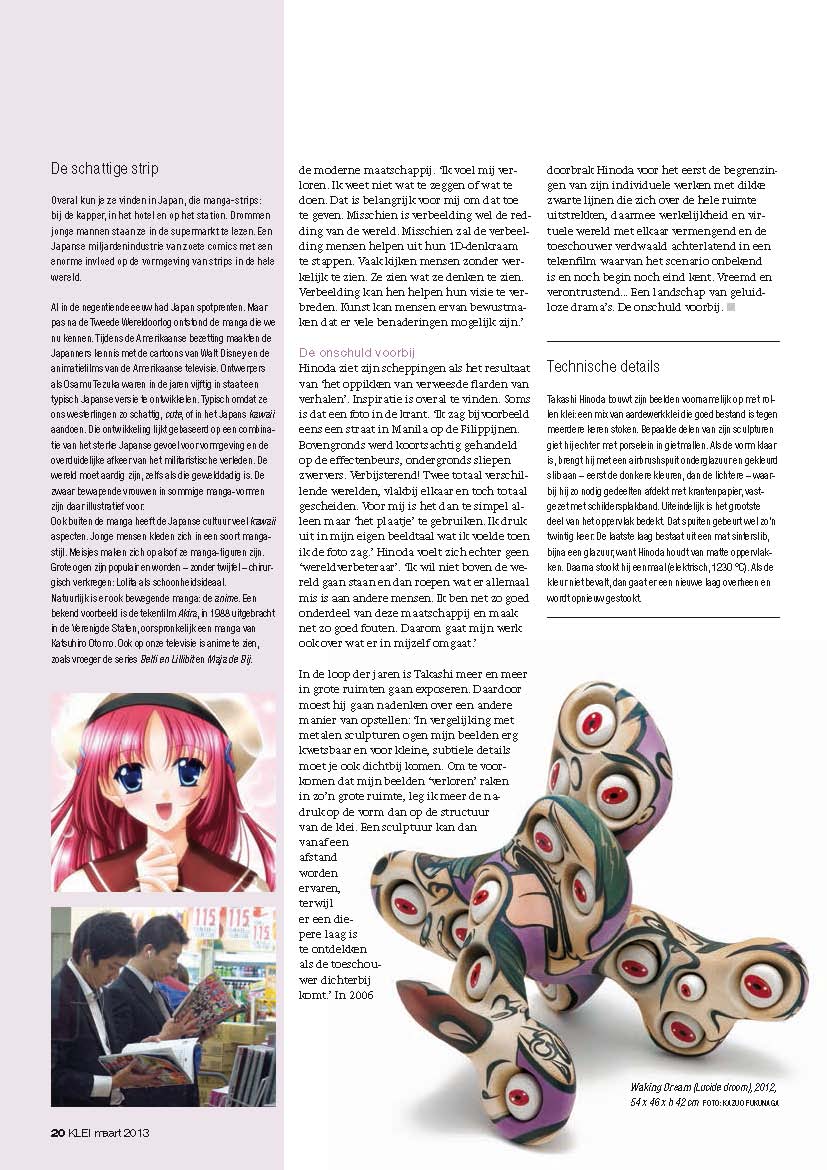

His work alternates between 2D and 3D and is also in other aspects difficult to categorise: paintings, ceramics or design? Takashi Hinoda took the Japanese manga and anime from their 2D-frame and transformed them into 3D-reality. In ceramics. ‘2.5D’ he calls them himself.

By Yna van der Meulen

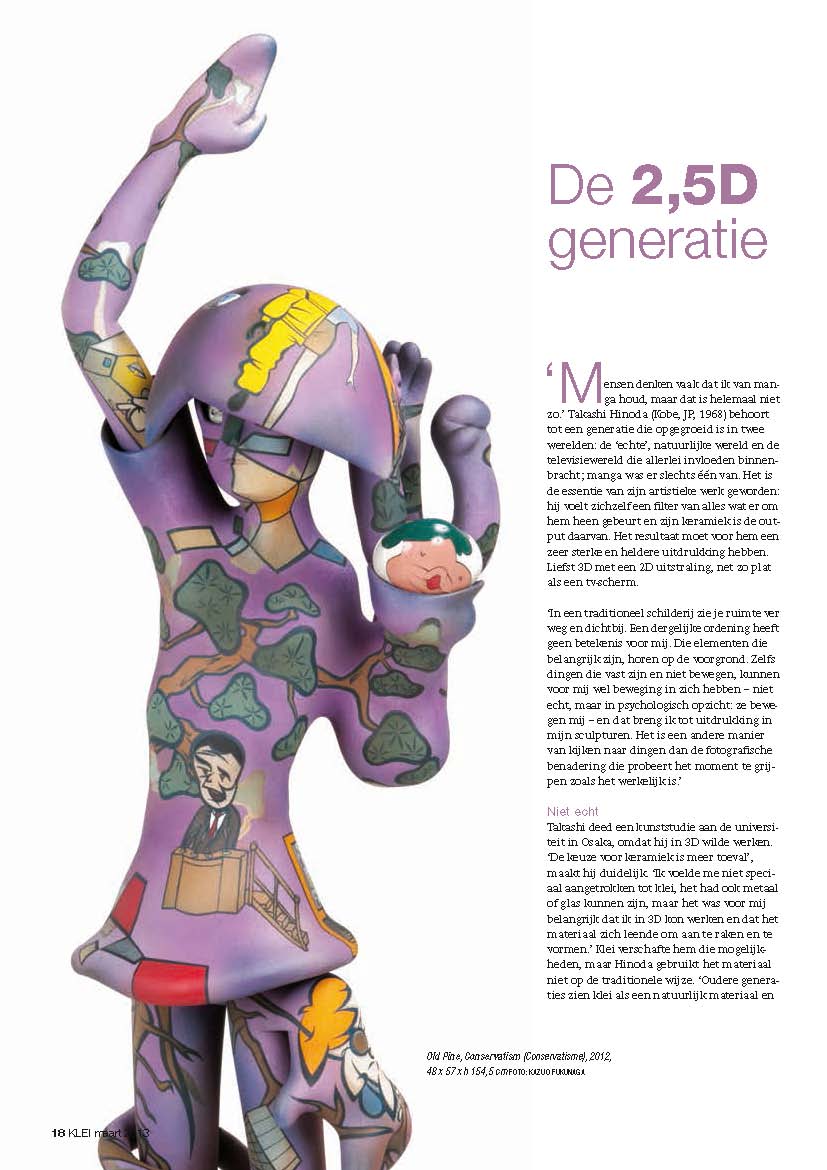

Takashi Hinoda (Kobe, JP, 1968) belongs to a generation that grew up in two worlds: the ‘real’, natural world and the television world that brought in all kinds of inputs; manga was just one of them. It would become the essence of his artistic work: he feels like a filter of everything that is happening around him and his ceramics is the output. To him the result must have a strong and clear expression. Preferably 3D with a 2D impact, just as flat as a television screen.

‘In a traditional painting there is space far away and close by. But this order has no meaning to me. Meaningful things have to be at the front. Even things that are stationary and don’t move, can have movement in them – not in reality, but in a psychological way: they are moving to me – and that is what I express in my sculptures. It is a different way of looking at things from photography which tries to grab a moment as it is.’

Takashi studied ceramics at the university of Osaka, because he wanted to work in 3D. ‘My choice for ceramics is just a coincidence’, he clarifies. ‘I was not especially attracted to clay, it also could have been metal or glass, but it was important to me that I could work in 3D and I wanted to have some kind of material that could be touched and formed.’ Clay provided him with those possibilities, but Hinoda doesn’t use the material in a traditional way. ‘Older generations may look at clay as a natural material and they probably try to retain the surface and the nature of the material. But people who grew up with television, are used to go to a supermarket to get food, where everything is packed in plastic so everything looks like it has the same texture. My generation was trained to have clean hands and is not used that things have a texture for instance. For me clay is also an artificial material; I want to hide its nature, to eliminate the texture, the constraints of the clay. But nevertheless there will always remain something that looks like ceramics.’ The consequence is that his work is often characterised as: ‘This is not at all ceramics!’

After his studies Takashi made figurative and non-figurative work – especially geometrical forms – and he discovered that while making figurative work people reacted differently from when sculptures weren’t figurative. ‘The distance is smaller between a figurative sculpture and the viewer. People understand those sculptures. Look at figures with a religious meaning, like Jesus Christ, which want to transmit a religious feeling.’ For Hinoda it is important to stay close to reality with his sculptures, but not too close. Therefore he is making a big effort to use symbols. In the beginning he tried to avoid that an eye looked like an eye. ‘This might be confusing to the viewer, but that is not my intention. I am the one who is confused when I look around me. There are many things around me that I don’t understand and that is quite disturbing to me.’ Takashi wants the viewer to be able to look at something in a more complex way. Perhaps establish similar feelings as he has himself. ‘Nowadays people expect everything to be easy to understand, people don’t want to think deeply about things, even concerning political opinions. I am not trying to force thinking in a complex way, but if I can get people to start thinking… Maybe as far as to have them realise that they can’t understand everything.’

Hinoda was 25 when a big earthquake distroyed his home town Kobe; at that moment he himself was in Shigaraki for an artist-in-residence stay. In that same period there were attacks with nerve gas in the Tokyo subway. ‘It was a period when I myself was trying to find out what to do with my life. A that time already I experienced what it means when everything collapses. How easily everyday life may fall apart. Now I feel the same. Already for a long time I have been feeling normal daily life going on, at the same time knowing that it might disappear at any time… Nothing is self-evident. In Japan we are constantly reminded of that.’

Hinoda is not only very much aware of the enormous powers of nature, he has also a fundamental feeling of despair about modern society. ‘I feel lost. I don’t know what to say or to do. It is important to me to admit this. Maybe imagination is the salvation of the world. Maybe imagination will help people to stop thinking too much one-dimensionally. People often look at something without really seeing. They see what they already have in mind. Imagination can help to broaden their vision. Art can make people aware that there are many ways of thinking.'

Hinoda thinks of his own creative acts as ‘the work of picking up the scattered remains of stories’. Inspiration can be found anywhere. Sometimes it’s a picture in a newspaper. ‘I once saw a picture of a street in Manila on the Philippines. Above ground there were many people dealing in a stock market; below it poor people were sleeping. It was so confusing! Two totally different worlds, at such a short distance, without any connection between them. It would have been too simple to just use this picture. I expressed this in my own language: what I felt when seeing this.’ Hinoda doesn’t feel himself an idealist trying to improve the world. ‘I think it is wrong to stand on a higher ground and then criticise other people, because I am part too, I make mistakes too. So, my works include what goes on in myself too.’

He more and more exhibits in big spaces. Therefore he had to think very much about a different way of exhibiting: ‘Compared to metal sculptures my works look very fragile and you have to stand very close to see small, sensitive details. My sculptures might get ‘lost’ in a big space, that’s why I try to emphasise on the form, rather then on the structure of the clay. This way a viewer can experience a piece from a distance, come closer and then see a different layer.’ In 2006 he crossed the boundaries of his individual sculptures with black outlines that stretch into the exhibition space, mingling real and virtual worlds and leaving the viewer lost in a comic with an unknown scenario and no beginning, no end… Uncanny and disturbing… A landscape of silent dramas. No more children’s stories…

Takashi Hinoda coils his sculptures for 90%, using a mix of stoneware clay that can be fired and refired again and again. However some parts of his sculptures are cast with porcelain in moulds. As soon as the form is ready, he sprays colours using airbrush: underglaze and coloured slips – first the darker colours, then the brighter ones – whilst covering parts with newspaper and tape. At the end almost the whole surface is covered. There may be a total of 20 layers. The last layer is a mat sinter slip, almost a glaze: Hinoda likes mat surfaces. Then he fires the piece on 1230 degrees in an electric kiln. When he is not satisfied about a colour, he just sprays another layer and then fires it again.

Courtesy of keramisch magazine KLEI

彼の作品は2次元と3次元のあいだを交互に行き来する。そしてまた、絵画であるか、陶芸であるか、デザインであるか、ジャンル分けできないような、別の様相を見せる。日野田崇は日本のマンガやアニメを取り上げて、それらを2次元の枠から3次元の現実へと変身させている。それを彼自身は《2.5次元》と呼んでいる。

ヤナ・ヴァン・ダー・ミューレン 記

日野田崇(日本/神戸市1968年生まれ)はふたつの世界で育った世代に属している。ひとつは、《現実》の自然の世界で、もうひとつはTVの世界、あらゆる種類の入力であり、マンガはそのひとつに過ぎない。それは彼の芸術作品の本質になった。彼は身の回りで起こるすべてのフィルターであり、彼の陶芸作品は出力である。彼にとって、結果は明快な表現、おそらく3次元は2次元のインパクトをともなっていなければならない。そう、TVのスクリーンのように。

「伝統的な絵画なら遠景と近景の空間がある。だが、この法則は僕には意味がない。意味のあるものは前面に出てこなければならない。動かないものでさえ、動くことができる。現実にではなく、心理的な意味で、僕にとっては動いているんだ。そういうものを彫刻の中で表現している。瞬間をそのまま掴もうとする写真などとは違うものの見方なんだ。」

崇は大阪の大学で陶芸を学んだ。彼は3次元の仕事がしたかったからだ。「僕の陶芸への選択はまったくの偶然だった。」彼ははっきりと言う。 「僕は特別に土に惹きつけられたわけではなかった。別に金属でもガラスでも良かったのかもしれない。しかし、立体の仕事ができたということは僕にとって重要だった。そして触れることができて、かたちづくることのできるような、なんらかの素材が必要だった。」 土は、そういう可能性を彼にあたえた。しかし日野田は素材を伝統的なやり方では使わない。「より年長の世代は土を自然の素材としてみるだろうし、素材の生理や肌あいを保っておこうとするだろう。しかし、TVで育った世代の人間は、食べ物を手に入れるならスーパーへ行くだろう。そこへいくと、何でもビニールで包装されていて、すべてが同じ質感に見える。僕の世代はいつも手をきれいに洗いなさいとしつけられていて、ものの質感を感じるようなことに慣れていない。土は僕にとっては人工的な素材でもある。僕はその性質を隠したい、質感をおさえて、土を抑制したい。しかし、それでもなお、なにか陶らしさというものがいつも残る。」 結果的に彼の作品はしばしば「全然陶芸じゃない!」と性格づけられることになる。

卒業後、彼は具象的な作品と、非具象的な作品、とくに幾何学的な作品を制作した。そして彼は、具象的な作品をつくっていたときのほうが、彫刻が具象的でなかったときとは違って、人が惹きつけられていることにきづいた。「具象的な彫刻作品のほうが観客に近しい距離を持てる。人はそういった彫刻を理解する。宗教的な意味を持つ像、キリスト像のようなものを見ると,宗教的な情感が伝わるだろう。」日野田にとって、彫刻で現実に近いところに留まることは重要ではあったが、近づきすぎないことも重要であった。それゆえ、彼はシンボルを使うようつとめている。最初、彼は眼のように見えるかたちを避けようとしていた。「これは観る人を混乱させるかもしれない。しかし、それは僕の意図するところではない。世の中を見まわしたとき、僕もまた混乱する人間の一人だ。多くのものごとがあるけど、僕も分からないし、まったく不安なんだ。」崇は人々に複雑なものの見方をできるようになってほしいと思っている。彼自身が感じているのと似た感情を確立すること。「いまや、人は何にでも分かりやすいものを期待する。政治的な意見でさえ、深く考えるのを嫌う。僕は複雑なもの見方を強制しようとしているのではないけれど、ちょっと考えるきっかけにしてほしいと思っている….たぶん、よくても、すべてのものごとが分かっているわけではないのだということに気づいてもらうところくらいまでだろう。」

故郷である神戸の街を大きな地震が襲ったとき、日野田は25歳だった。そのときは、彼自身はアーティスト・イン・レジデンスで信楽に滞在していた。同じ頃に、東京の地下鉄で神経ガスがばらまかれるという事件があった。「その頃は、僕自身どのように人生を生きていくべきか見いだそうともがいていた時期だった。そのとき、僕はすべてが崩壊するというのはどのようなものかすでに経験した。日々の生活が如何に容易く崩れ去るのかを。いまでもそう感じる。長い間、いつもの毎日は過ぎていくように感じていたが、同時にいつそれが消え去ってもおかしくないことも、すでに知っていたのだ。自明なものはなにもない。日本人は、いつもことあるごとにそのことを意識してきた。」

日野田は自然の巨大な力を知るだけではなく、現代社会への絶望を根源的に感じている。「僕は迷っている。何と言っていいのか、どうしたら良いのか分からない。だけど、このことを認めるのは大事なことなんだ。おそらく想像力は世界の救済になりうる。想像力は人々が一面的に物事を考え過ぎることを止めるのに役立つだろう。人は、しばしばものごとをよく見ずに考えることがある。みんな、ものごとを見ているのではなしに、自分の心にあらかじめ浮かんだものを見ているのだ。想像力があれば、ものの見方がひろがるだろう。芸術は多様な考え方がありうることを人々に気づかせることができる。」

日野田は自分の創作行為を「バラバラになった物語の残滓を集める作業」だと考えている。インスピレーションとなるものはどこにでもある。ときには新聞の写真であったりする。「フィリピンのマニラの通りの写真を目にしたことがある。地上には証券取引をやるたくさんの人々がいて、その下には貧民達が眠っていた。なんという、頭がおかしくなりそうな様子だろうか!完全な二つの別世界が、こんなに近い距離のうちにある。その間にはなんのつながりもない。その絵面をそのまま使うのはあまりにも単純すぎるだろう。僕はこれを自分の言語で表現した。僕が感じたのはこんな感じさ。」日野田は、自分のことを、世の中を良くしていく理想主義者とはとらえていない。「高みに立って他者を批評するのは間違っていると思う。なぜなら、僕もその一部だから。僕もまた過ちを犯す。だから、作品は、僕自身のことを含めてどうなっているのかをあらわしているんだ。」

彼は展示を重ねるうちに、大きな空間を扱うことも出てきた。それゆえ、彼は新しい展示方法について様々に熟慮しなければならなくなってきた。「金属の彫刻などと比較したとき、僕の作品はとても脆く見えるし、小さく繊細な細部を見るには近くに立たなければならない。僕の作品は大きな空間で《迷子》になっているように見えるかもしれない。だから僕は、土の構造よりもかたちのほうをより強調しようとしている。この意味では観客は離れたところからでも作品を体験でき、そのあともっと近くに来ると、違う層を見ることになる。」2006年には彼は独立した彫刻の領域を横切り、黒い線を用いてそれを展覧会の会場にまでのばしていった。現実と仮想が混ざりあうことで、未知の背景を持ったマンガの中に観客を迷い込ませた。そしてそこには始まりもなく、終わりもない.....気味悪く、不安で、無言劇の風景だ。もはやそこに童話はない。

日野田崇は9割がたの彫刻を紐づくりで制作している。土は混合された陶土で、繰り返し焼成することができる(電気炉焼成 1230℃)。いくつかの作品の部分は型成形の磁土でできている。 かたちができると、エアブラシを使って色を吹きつける。部分を新聞紙やテープで覆いながら、はじめは暗めの色、そしてだんだん明るい色調のものへと塗っていく。最終的には表面全体が覆われる。色について満足できない場合はさらに層を塗り重ね、焼成を繰り返す。最後には全部で20層くらいになる。最後の層はつや消しの熔化化粧土で、ほとんど釉薬のようになる。日野田はつやのない表面を好む。